The Pewenche Summerlands: Documenting Chedungun

Mural drawing by Pewenche children. Photo by Pablo Fuentes, 2020. Click on image to access collection.

| Language | Chedungun (Mapudungun) (ISO639-3:arn) |

| Depositor | Pablo Fuentes |

| Affiliation | Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción |

| Location | Chile |

| Collection ID | 0631, 0693 |

| Grant ID | SG0574, IPF0393 |

| Funding Body | ELDP |

| Collection Status | Collection online |

| Landing Page Handle | http://hdl.handle.net/2196/728f34b9-55c7-4fe2-ae7c-bd029eaf8dcc |

Blog Post

In English: Community Members Bio: Sisters Sonia and Mónica Vita

En español: Entrevista con las hermanas Sonia y Mónica Vita

Summary of the collection

The collection offers a documentation of Chedungun, the regional variation of Mapudungun that is spoken by the Pewenche people. Most part of the audio-visual material was recorded in journeys in the vicinity of the Andean valley of Butalelbún, in the Alto Biobío region, southcentral Chile. Our aim has been to document the Pewenche transitional lifestyle and language use. The collection gathers both naturally occurring and elicited communicative events during several seasonal ascents to the Pewenche summerlands of Kochiko (the Andean highlands that are occupied by a small group of Pewenche families for transhumance-related activities).

Group represented

‘Pewenche’ means ‘people of the pewen’ (= the Araucaria araucana tree). They constitute a semi-nomadic indigenous group that lives in the Andean valleys of south-central Chile and adjacent areas of Argentina. Their native language is Chedungun, a regional variant of Mapudungun (arn, Mapu1245).

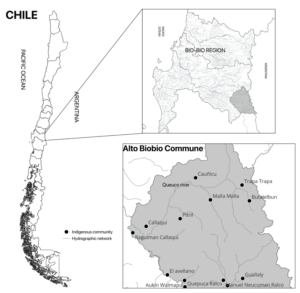

Our documentary work has been circumscribed to some of the communities in the Alto Biobio Commune, in the south-east area of the Bio-Bio region, Chile (see map below). The surrounding landscape of the region is comprised of river terraces, semi populated mountainsides, araucaria forests and occasional Andean plateaus, all of which the Pewenche travel regularly on horseback. An estimate of the Pewenche population in the twelve communities of the Alto Biobío region is roughly 5,000. The percentage of fluent speakers of Chedungun within those communities has not been pondered with precision, although it is evident that the number is severely decreasing.

Map of the Alto Biobio Commune and the Pewenche communities. Source: Cristian Alister.

A relevant fact about the Pewenche is that they constitute the only indigenous group within the Araucanian sphere that has been said to have an independent origin. Studies suggest that the Pewenche transited for centuries through the nomadic routes on both sides of the Andes. Crucially, this migratory element is still a tangible characteristic of the lifestyle of many modern Pewenche families and makes salient one relevant fact for any documentation initiative in this ethnographic sphere: namely, that of all the groups that comprise the Mapuche universe, the Pewenche people are the only ones that carried (and still carry) a fair degree of nomadic lifestyle. More concretely, migratory practices linked to animal husbandry and gathering can still be attested today in what seems to conform a bipartite annual cycle, each of the two intervals occurring at a different seasonal residence (low valleys for the winter and high grasslands for the summer).

The summerlands –the highlands that are occupied by the Pewenche families between the melting of snows and the arrival of winter– is a perdurable sign of the mentioned migratory lifestyle, and are closely linked to the traditional activities of the Pewenche. Due to their geographical location, the summerlands preserve an abundance of the millenary forests of pewen and remains more impermeable to modern elements, such as roads for motorized vehicles, electricity, internet, etc. This results in a dual seasonal residence with a relatively clear division of lifestyle: while the winterlands are rooted in locations that are connected by a main road to more urbanized locations (with all its implications), a summerland typically constitutes a more isolated valley at which the Pewenche families can carry their traditional activities in a more pristine form.

Pewenche summerland of Kochiko. Photograph: Pablo Fuentes

No matter how crucial for their cultural identity, this migratory element has not been immune to the multiple endangering factors of modern times. On the contrary, the heritage value of the Pewenche summerlands has been once and again defiled by state policies and socio-economic circumstances. That the Pewenche migratory practices are approaching their last generational stages is an undeniable and disturbing fact that can only be overcome by raising a serious voice of concern of what these cultural goods represent. The urge of documenting the speech events surrounding the Pewenche migratory cycle emerges, then, from two intertwined factors: the endangerment of their language and the endangerment of their lifeforms.

Language information

The native language of the Pewenche people is Chedungun, a regional variant of Mapudungun (arn, Mapu1245). ‘Chedungun’ simply means ‘the language of the people’ (che = people; dungun = language). In the linguistic literature, the language has been referred to as ‘Pehuenche’, the Spanish denomination for the Pewenche people. We have not adhere to this denomination and have used the term Chedungun instead. The language is currently spoken by less than 5000 speakers along the Alto Biobio valleys.

Special characteristics

One of the members of the documentation team, depositor Sonia Vita Manquepi, is a linguist and native speakers of Chedungun. Her role has been crucial for both the materialization of this project and the community engagement, which includes her own parents, sisters and brothers. In the same vein, main field assistant Mónica Vita Manquepi has contributed with an invaluable work during the coronavirus pandemic, self-documenting her native language with interviews to members of her own family. This results in a rich recorded testimony of the ethnographic and sociocultural background of the Pewenche summerlands. We believe that the material constitutes a novel source for anthropological and historical research, given that such testimony is offered by prime participants in their own language.

Collection contents

In its current version, the collection gathers approximately 15 hours of recorded language use. The deposited data register both naturally occurring and elicited communicative events. A significant portion of the material was recorded during the ascents and stays in the Pewenche summerland of Kochiko. The collection also contains a small but growing photographic catalogue of the summerland, which will include in time both documentary landscape and portrait photographs.

Among the activities recorded in the audio-visual data we can mention:

- the recollection of fruits and seeds

- animal care and grazing

- weaving

- cooking

- use of medicinal herbs

- traditional storytelling (epew)

- journeys through land and description of landscape

- mate drinking and reminiscence of past events

At this stage, part of the material is undergoing the process of annotations, which will include transcription, translation into English and Spanish and an incipient grammatical analysis. A showcase of 20 minutes will be available soon. It is expected that the annotated material substantially increases in 2023.

Other information

Along our project, we have built a documentation team of four members: linguist Pablo Fuentes, sisters Sonia and Mónica Vita, and Luis Crespo. Three members of the team are Pewenche and native speakers of Chedungun. Sonia Vita possesses a postgraduate degree in linguistics and teaches and translates the language regularly. The multicultural character of the team has been crucial for both the materialization of this project and its collaborative workflow. Community engagement has been key and has led naturally to self-documentation practices, which have been conducted by Mónica Vita and Luis Crespo. The result is a rich non-intrusive testimony of the ethnographic and sociocultural background of the Pewenche lifestyle, especially the summerlands.

Pablo Fuentes and Sonia Vita have written an article on the experience of the documentation in its first stage (Stage One). If you are interested, please access the authors’ manuscript, accessible through this link: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/b256eb4c-2f95-49f7-835d-268502df60d5.

Pablo Fuentes wrote about this work in two ELAR Blogs: In English: https://elararchive.org/blog/2020/11/12/community-members-bio-sisters-sonia-and-monica-vita/ En español: https://elararchive.org/blog/2020/11/20/entrevista-con-las-hermanas-sonia-y-monica-vita/

Acknowledgement and citation

Thanks to all the members of the Vita Manquepi family in Butalelbun for several endearing journeys to the Pewenche summerland of Kochiko. Their work and collaborative spirit throughout the project provided us the necessary newen for such a wonderful experience.

We also thanks colleagues Marisol Henriquez and Jorge Lillo, from Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción, for their interest in our projects and initiatives. We also thank the wonderful and motivating staff at ELDP and ELAR, for their constant support and guidance.

To refer to any data from the collection, please cite as follows:

Fuentes, Pablo & Sonia Vita Manquepi. 2019. The Pewenche Summerlands: Documenting Chedungun. Endangered Languages Archive. Handle: http://hdl.handle.net/2196/e026920b-f65e-4a1e-bc5e-e7ab3bd8968a. Accessed on [insert date here].